Today is the end of the TBR Double Dog Dare and I confess I fell at the final hurdle. Apart from a couple of audiobooks which were only to keep me company while I knitted, I had managed to stick to books that were either owned or in my library request list since the 1st of January .... until Friday. I finished The Tiger's Wife and picked up a library book that was waiting, something worthy and scientific that Brainpickings had recommended, and I couldn't find a moment's interest in it. 'Care of Wooden Floors' by Will Wiles had been bought with my Christmas money and had been waiting patiently on the windowsill, I succumbed. It has only taken me two days to read it. I will be lending it to lots of people.

It sounds like a really dull premise for a story: our unnamed protagonist goes to an unnamed east European city to 'flat-sit' for a friend. The title is not that promising either. Don't be fooled. The friend, Oskar, is a control-freak classical composer, and they have known each other since university days. The narrator is a writer who aspires to move from copywriting local authority leaflets to something slightly more creative, and has hopes that a couple of weeks in the seclusion and calm of his friend's flat might be just the impetus he needs. Lets just say that things don't work out quite as he hoped. There will be no spoilers as any disclosure of the events that follow would be unforgivable. I did get to the stage where I was anticipating what was going to happen next; at one point I had to shut the book and leave the room as my precognition was creating excessive anxiety as the situation in the flat spirals out of control. He is a fish out of water, isolated in a strange country where he can't communicate with the locals, you watch fascinated as his sense of reality slowly unravels. The instructional notes from Oskar that are secreted around the flat are wonderful, managing to still pop up unexpectedly even when you think you know how his brain works. I can tell you that red wine and cats are the dominant players in the drama.

Schadenfreude: the quote on the front from The Independent review is very accurate, there was much pleasure derived from someone else's misfortune. I never laughed aloud at a book as much as I did this afternoon. I kept expecting him to just give up and leave, but no, everything he did, all the choices seemed to be about the worst thing you could decide in any situation. This was what made it so funny, it wasn't just things happening, it was his decisions that forced the situation through more and more bizarre turns. He mentions Schrodinger early in the story, I don't recall exactly, but then much much later we have the situation where he thinks; "As long as Oskar didn't know about the cat, and the wine, I had a few more throws of the dice. The cat, in fact, was not dead until he learned it was dead". (p.179) The whole book becomes a weird twisted Schrodinger experiment, if Oskar doesn't know something then he can continue to pretend to himself that it hasn't really happened.

Ok, quotation time, because it was not just an incredibly clever story with beautifully crafted characters, it is exquisitely written. There were moments when I felt there was excessive adverb usage, and sometimes he dwelled over long on the description, but I forgave him completely.

His first view of the wooden floor;

"The beautiful wooden floor didn't have nails, it had a manicure." (p.5)

The furniture in the flat;

"It was one of those chairs that had a sad aura of futility, a regret that it had been designed to be sat in and never was, and had often suffered the indignity of simply being a prop to drape clothes over." (p.10)

Oskar's approach to interior decor:

" 'A room is not just a room. A room is a manifestation of a state of mind, the product of an intelligence. Either conscious' - and he dropped dramatically back into his armchair, sending up a plume of dust and cigarette ash - 'or unconscious. We make our rooms, and then our rooms make us.' " (p.34)

In the local market place;

"Never before have I truly understood the full significance of the word 'heaving' in relation to masses of humanity, but the market was heaving; one's direction of travel was utterly limited by crowd consensus, so that whole quarters were closed off by contrary flows of traffic, and often your course was entirely away from your intended direction, dictated only by a new shudder of peristalsis in the folds and crevices the stalls left for their wretched customers." (p.38)

On finding a note from Oskar in a CD case inviting him to enjoy the music, this is an early sign of how his isolation is beginning to show the cracks in his sanity;

"How nice of him, I thought, or at least began to think as the sentiment stopped dead in my mind, like the needle being ripped off the surface of a old vinyl LP. This wasn't nice, or if it was nice it was nice in a sinister spectrum of nice that I did not have the ability to see." (p.65)

The light in the study;

"Even the light here was different - it seemed to slant most attractively, italicised for emphasis, soft and pale as vellum, enlivened by the pirouetting points that rose from the seams of dust cultivated by stockpiles of paper. It was restful, but wholly awake." (p.162)

I was going to put in a lovely quote where he makes a circuitous justification for why none of the events are his fault, but unfortunately it gives far too much away. The crux of the book is the interplay of the two characters; even though Oskar is not there except for brief flashback moments to their early friendship, his personality is the dominant one, and our protagonist struggles to assert himself. And Oskar made me feel as if I am hardly neurotic at all. I was mistaken in my suspicions about the denouement, but the final twist of the plot was just perfect. Sometimes I find people's irrational behaviour in books to be annoying, but here it was logical and in character. I cannot fault this book, I am not sure everyone would find it as amusing as I did, but give it a try anyway.

Sunday, 31 March 2013

Welcome to the A to Z challenge 2013

Tomorrow begins the annual blogfest that is The Blogging from A to Z Challenge. Last year I decided to step out of my normal routine and every day through April I wrote 100 words flash fiction pieces, starting with A for Adultery and ending at Z for Zealot. This year I have decided to explore an aspect of writing that is very close to my heart - children's literature. Looking up the word 'literature' I find this: written works, especially those considered of superior or lasting artistic merit. I spent many, many years reading children's books and during that time I tried very hard to read things to my children that were good stories, well told and (most essentially I feel) well illustrated; good pictures can really make a story book. I confess as the years passed I became a bit of a children's book snob, there are so many out there that are just not worth reading. This month I aim to introduce you to some of our favourites and hope to inspire and encourage parents. The photo here shows my children, from the left, Lewis, Creature, Tish and Jacob (all now adults) underneath a spiders web of yarn that they created that filled our entire house.

(visit here to my reflections post from last year's challenge.)

Friday, 29 March 2013

Dunky Jumpy mark 2 - Fibre Arts Friday

I made Dunk his first jumper over two years ago, and really he barely deserved a second one considering how little he has worn it, though on reflection I can see how short it is (and his hair has changed a lot too!). This new one was knitted in some merino cashmere aran from Kingcraig Fabrics (where I also bought yarn for my yellow cable jumper) and the pattern is Italianate Cables from Interweave press (Ravelry project link). It has been a huge slog as I started it in a fit of enthusiasm after doing my yellow one way back in September last year and it has languished very badly, making me feel guilty and unable to start any new projects.

However have also returned a little to the hexipuffs and been trying to knit one a day, in the hope that if Creature gets into drama school it will be ready for her to take away with her, the tally is probably around 220 now.

However have also returned a little to the hexipuffs and been trying to knit one a day, in the hope that if Creature gets into drama school it will be ready for her to take away with her, the tally is probably around 220 now.

(Please pop over the Fibre Arts Friday and visit other creative endeavours)

Truth and Beauty

Ann Patchett's wonderful reading of her book 'Truth and Beauty' has accompanied my knitting and sewing up, and then cooking dinner yesterday. The book is the story of her friendship with a fellow writer and poet called Lucy Grealy, with whom she shared a house when they were studying together in Iowa. It is the story of Lucy, because her physical and emotional tribulations dominate their friendship, but we learn as much about Ann as we do about Lucy from the story, and it is about the twenty years of their lives that was shared so intensely.

Linked to the wiki page is this Guardian article written by Lucy's sister Suellen, in which she describes feeling that their family's grief has been hijacked by Ann's version of what happened to Lucy. I was a little taken aback by the accusation because the book casts no judgement on Lucy's family nor accuses them of any failings, she didn't write about Lucy's family because she didn't know them; it is purely about the intensity of their friendship and as such the loss that her death inflicted on Ann, surely such a friend has as much need to grieve as the family. This sentence seems to sum up a tinge of bitterness Suellen feels towards someone who was possibly closer to her sister than she was: "My sister Lucy was a uniquely gifted writer. Ann, not so gifted, was lucky to be able to hitch her wagon to my sister's star." I felt this is a terrible and erroneous accusation, both about Ann Patchett's writing and her friendship with Lucy. It's funny, even though the book is told so wistfully in the past tense, with such exquisite tenderness and fondness, it wasn't until the pain killers and then the heroin get mentioned that it even occurred to me that she was going to die. You can't help but fall a little in love with Lucy yourself as you listen, she is just one of those people who throws themselves at life, the ultimate carpe diem character. She is somewhat wild and carefree, incautious in all her endeavours. She throws herself into Ann's arms on their first meeting as if they had always loved each other and in assuming that she does what else can Ann do but love her. And it turns out she can enchant horses and cats as easily as people. The story follows them as they try to write, to teach, to find meaningful work and to find love, an eternal quest and struggle for Lucy. Following childhood cancer Lucy was left disfigured, and her desire to 'fix' herself is something the book catalogues in detail, it unavoidably becomes Lucy's defining feature and Ann's role to support and encourage her throughout the process. It leaves you a little in awe of how much suffering one person is capable of enduring.

A couple of things I wrote down that I liked: this one was not about Lucy but about Elizabeth McCracken, she and Ann both completed manuscripts and printed them out together, I liked the exuberant sense of achievement at having produced some tangible writing:

"We stood on our books to see how much taller they had made us."

And the other, when she is helping Lucy to tidy and declutter her home prior to another round of surgery, they are sorting through her book and music collections. I like what it says about Ann, I think I would like her because I really get this;

"I had the supreme pleasure of putting all the discs back in their correct cases."

In the face of an avalanche of books about love and romantic relationships often the importance of friendship is sorely neglected, and this is a real homage to the value of friends, written as the title claims, with truth and beauty.

Linked to the wiki page is this Guardian article written by Lucy's sister Suellen, in which she describes feeling that their family's grief has been hijacked by Ann's version of what happened to Lucy. I was a little taken aback by the accusation because the book casts no judgement on Lucy's family nor accuses them of any failings, she didn't write about Lucy's family because she didn't know them; it is purely about the intensity of their friendship and as such the loss that her death inflicted on Ann, surely such a friend has as much need to grieve as the family. This sentence seems to sum up a tinge of bitterness Suellen feels towards someone who was possibly closer to her sister than she was: "My sister Lucy was a uniquely gifted writer. Ann, not so gifted, was lucky to be able to hitch her wagon to my sister's star." I felt this is a terrible and erroneous accusation, both about Ann Patchett's writing and her friendship with Lucy. It's funny, even though the book is told so wistfully in the past tense, with such exquisite tenderness and fondness, it wasn't until the pain killers and then the heroin get mentioned that it even occurred to me that she was going to die. You can't help but fall a little in love with Lucy yourself as you listen, she is just one of those people who throws themselves at life, the ultimate carpe diem character. She is somewhat wild and carefree, incautious in all her endeavours. She throws herself into Ann's arms on their first meeting as if they had always loved each other and in assuming that she does what else can Ann do but love her. And it turns out she can enchant horses and cats as easily as people. The story follows them as they try to write, to teach, to find meaningful work and to find love, an eternal quest and struggle for Lucy. Following childhood cancer Lucy was left disfigured, and her desire to 'fix' herself is something the book catalogues in detail, it unavoidably becomes Lucy's defining feature and Ann's role to support and encourage her throughout the process. It leaves you a little in awe of how much suffering one person is capable of enduring.

A couple of things I wrote down that I liked: this one was not about Lucy but about Elizabeth McCracken, she and Ann both completed manuscripts and printed them out together, I liked the exuberant sense of achievement at having produced some tangible writing:

"We stood on our books to see how much taller they had made us."

And the other, when she is helping Lucy to tidy and declutter her home prior to another round of surgery, they are sorting through her book and music collections. I like what it says about Ann, I think I would like her because I really get this;

"I had the supreme pleasure of putting all the discs back in their correct cases."

In the face of an avalanche of books about love and romantic relationships often the importance of friendship is sorely neglected, and this is a real homage to the value of friends, written as the title claims, with truth and beauty.

Thursday, 28 March 2013

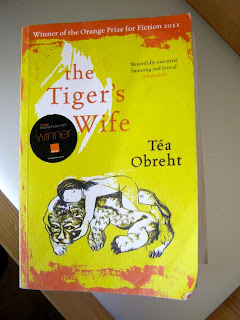

The Tiger's Wife - TBR Pile Challenge

The Tiger'sWife by Téa Obreht was the Orange Prize winner in 2011 (continuing an ad hoc challenge to read all the winners) and is also the sixth book from my TBR pile challenge 2013. What struck me most was the apparent youth of the author and the way the book has such various and tangled threads, something you would expect from someone with more life experience. It's one of those books that makes you think that in reality you have to have lived an interesting life, or at least had a culturally interesting background, in order to write a novel; the author was born on Yugoslavia and moved from there to escape the conflict, ending up in America; her writing is obviously informed very much by the traditional storytelling of her childhood.

So the story is about family, history, mythology and superstition. And war, but not war as in bombs and guns, but in the impact it has on a population and the culture. It takes place against the backdrop of the war that tore apart the country that was Yugoslavia but harks back to the period of World War Two and the childhood of our narrator's grandfather. I was a little confused for a while, because in fact there are two tigers; the one she visits with her grandfather, and the other that escapes from the zoo during the war and comes to find itself living outside her grandfather's village. The story moves back and forth in time, via the stories that he grandfather tells her about the deathless man and the tiger's wife. There are long digressions, like the story about Luca, who's only purpose seems to be to explain the presence of the young girl who becomes the tiger's wife, but I liked that about the book, it gave the whole tale a level of complexity that was very engaging. Further suggested reading in the back listed One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and though I never managed to finish that book I could see the link, both in the themes and the style. This book is similarly about history and dramatic change but also the unchanging nature of communities, about how myths and stories bind people together and create continuity. But it is also about the negative side of mythology and superstition; the men digging in the village for the body of a relative to lift a curse, and how the tiger's wife comes to symbolise the fear that the villagers have of the unknown and their desire to destroy the tiger and her is the only reaction that they can have to the situation.

Alongside the beautifully written story she makes some very interesting and astute observations of the effect of the war on a population (the second one here I found left me quite depressed, there is something hopeless about it):

"When your parents said, get your ass to school, it was alright to say, there's a war on, and go down to the riverbank instead. When they caught you sneaking into the house at three in the morning, your hair reeking of smoke, the fact that there was a war on prevented then from staving your head in. When they heard from neighbours that your friends had been spotted doing a hundred and twenty on the Boulevard with you hanging non too elegantly out the sunroof, they couldn't argue with there's a war on, we might die anyway. They felt responsible, and we took advantage of their guilt because we didn't know any better." (p.34-5)

"When your fight has purpose - to free you from something, to interfere on behalf of an innocent - it has a hope of finality. When the fight is about unraveling - when it is about your name, the places to which your blood is anchored, the attachment of your name to some landmark or event - there is nothing but hate, and the long, slow progression of people who feed on it and are fed it, meticulously, by the ones who come before them. Then the fight is endless, and comes in waves and waves, but always retains its capacity to surprise those who hope against it." (p.281)

I always enjoy feeling like I've learned something new when I read. The aforementioned Luka leaves his destiny of butchery (the chopping meat kind not the fighting kind) and goes off to find a new life as a wandering musician, playing the Gusla, which is one of these, a curious single stringed instrument (which you can hear being played here). He has a slightly idealised view of the life that he hopes to find, and it bought back down to earth rather abruptly:

"As to the musicians themselves, they were more complicated than Luca had originally expected, a little more ragtag, disorganised, a little more dishevelled and drunk than he had imagined. They were wanderers, mostly, and had a fast turnover rate because every six months or so someone would fall in love and get married, one would die of syphilis or tuberculosis, and at least one would be arrested for some minor offence and hanged in the town square as an example to the others." (p.195)

Anyway, having meandered though history for a while we return to the present, and a young woman trying to make sense of her grandfather's death and life, and the strange events going on in the orchard outside the house she is staying in. Really just a quote that I liked because of the image at the end, but on re-reading says something interesting about how dislocating death is:

"The heat of the day, compounded by my early morning in the vineyard, had caught up with me. I felt I'd waited years for the body to be found, though I'd only heard about it that morning - somehow being in Zdrevkov had changed everything, and I didn't know what I was waiting for anymore. My backpack was on my knees, my grandfather's belongings folded up inside. I wondered what they would look like without him: his watch, his wallet, his hat, reduced by his absence to objects you could find at a flea market, in somebody's attic." (p.232)

And another one, about death, because in many ways the story is about death, and what it means. It kind of sums up what went wrong in Yugoslavia:

"I married your grandmother in a church, but I would still have married her if her family had asked me to be married by a hodza. What does it hurt me to say happy Eid to her, once a year - when she is perfectly happy to light a candle for my dead in the church? I was raised Orthodox; on principle, I would have had your mother christened Catholic to spare her a full dunking in that filthy water they kept in the baptismal tureens. In practice, I didn't have her christened at all. My name, your name, her name. In the end, all you want is someone to long for you when it comes time to put you in the ground." (p.282-3)

All in all a lovely tale, in the traditional sense of the word; it felt as if I was reading something written much much longer ago.

So the story is about family, history, mythology and superstition. And war, but not war as in bombs and guns, but in the impact it has on a population and the culture. It takes place against the backdrop of the war that tore apart the country that was Yugoslavia but harks back to the period of World War Two and the childhood of our narrator's grandfather. I was a little confused for a while, because in fact there are two tigers; the one she visits with her grandfather, and the other that escapes from the zoo during the war and comes to find itself living outside her grandfather's village. The story moves back and forth in time, via the stories that he grandfather tells her about the deathless man and the tiger's wife. There are long digressions, like the story about Luca, who's only purpose seems to be to explain the presence of the young girl who becomes the tiger's wife, but I liked that about the book, it gave the whole tale a level of complexity that was very engaging. Further suggested reading in the back listed One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and though I never managed to finish that book I could see the link, both in the themes and the style. This book is similarly about history and dramatic change but also the unchanging nature of communities, about how myths and stories bind people together and create continuity. But it is also about the negative side of mythology and superstition; the men digging in the village for the body of a relative to lift a curse, and how the tiger's wife comes to symbolise the fear that the villagers have of the unknown and their desire to destroy the tiger and her is the only reaction that they can have to the situation.

Alongside the beautifully written story she makes some very interesting and astute observations of the effect of the war on a population (the second one here I found left me quite depressed, there is something hopeless about it):

"When your parents said, get your ass to school, it was alright to say, there's a war on, and go down to the riverbank instead. When they caught you sneaking into the house at three in the morning, your hair reeking of smoke, the fact that there was a war on prevented then from staving your head in. When they heard from neighbours that your friends had been spotted doing a hundred and twenty on the Boulevard with you hanging non too elegantly out the sunroof, they couldn't argue with there's a war on, we might die anyway. They felt responsible, and we took advantage of their guilt because we didn't know any better." (p.34-5)

"When your fight has purpose - to free you from something, to interfere on behalf of an innocent - it has a hope of finality. When the fight is about unraveling - when it is about your name, the places to which your blood is anchored, the attachment of your name to some landmark or event - there is nothing but hate, and the long, slow progression of people who feed on it and are fed it, meticulously, by the ones who come before them. Then the fight is endless, and comes in waves and waves, but always retains its capacity to surprise those who hope against it." (p.281)

I always enjoy feeling like I've learned something new when I read. The aforementioned Luka leaves his destiny of butchery (the chopping meat kind not the fighting kind) and goes off to find a new life as a wandering musician, playing the Gusla, which is one of these, a curious single stringed instrument (which you can hear being played here). He has a slightly idealised view of the life that he hopes to find, and it bought back down to earth rather abruptly:

"As to the musicians themselves, they were more complicated than Luca had originally expected, a little more ragtag, disorganised, a little more dishevelled and drunk than he had imagined. They were wanderers, mostly, and had a fast turnover rate because every six months or so someone would fall in love and get married, one would die of syphilis or tuberculosis, and at least one would be arrested for some minor offence and hanged in the town square as an example to the others." (p.195)

Anyway, having meandered though history for a while we return to the present, and a young woman trying to make sense of her grandfather's death and life, and the strange events going on in the orchard outside the house she is staying in. Really just a quote that I liked because of the image at the end, but on re-reading says something interesting about how dislocating death is:

"The heat of the day, compounded by my early morning in the vineyard, had caught up with me. I felt I'd waited years for the body to be found, though I'd only heard about it that morning - somehow being in Zdrevkov had changed everything, and I didn't know what I was waiting for anymore. My backpack was on my knees, my grandfather's belongings folded up inside. I wondered what they would look like without him: his watch, his wallet, his hat, reduced by his absence to objects you could find at a flea market, in somebody's attic." (p.232)

And another one, about death, because in many ways the story is about death, and what it means. It kind of sums up what went wrong in Yugoslavia:

"I married your grandmother in a church, but I would still have married her if her family had asked me to be married by a hodza. What does it hurt me to say happy Eid to her, once a year - when she is perfectly happy to light a candle for my dead in the church? I was raised Orthodox; on principle, I would have had your mother christened Catholic to spare her a full dunking in that filthy water they kept in the baptismal tureens. In practice, I didn't have her christened at all. My name, your name, her name. In the end, all you want is someone to long for you when it comes time to put you in the ground." (p.282-3)

All in all a lovely tale, in the traditional sense of the word; it felt as if I was reading something written much much longer ago.

Tuesday, 19 March 2013

Sarah Thornhill

Having failed to read a single book for Orange January and amid the announcement of this year's longlist for the newly renamed Women's Prize for Fiction I have spent the day on Sunday knitting and listening to 'Sarah Thornhill' by Kate Grenville. I just discovered on her website that this is the third in a trilogy of books about the early years of european settlement in Australia.

Written in the first person it tells the story of Sarah, youngest daughter in the family of an ex-convict who has made his fortune and provides for his family in relative comfort and security. Her childhood crush on the handsome Jack Langland becomes a doomed love affair and her life ends up following a path that starts out as an escape from her parents but becomes a life she freely chooses and values. But there are dark secrets buried in her family's past that eventually come to light. The story vividly encapsulates the troubled relations between the incomers and the aboriginal people, but it is also about families and what makes them, what binds them together and what divides them. Her voice is very immediate, not an old woman recounting the long ago but a young and vibrant character still troubled by the events that have plagued her growing up. I don't want to give too much of the plot away as there are many twists and turns to the events.

Kate Grenville's book The Idea of Perfection was my favourite from last year. Her stories seem to capture very well the thing that is distinct about Australia, not just the unforgiving environment but the impact it has has on the people who went there. She doesn't shy away from dealing with both the tensions between those transported and those who considered themselves true pioneers and the racial tensions that ensued from their invasion. Another wonderful book.

(I confess not from the TBR pilebut picked out so I could listen and knit, am not allowing myself to start a new project until Dunk's jumper is finished.)

Written in the first person it tells the story of Sarah, youngest daughter in the family of an ex-convict who has made his fortune and provides for his family in relative comfort and security. Her childhood crush on the handsome Jack Langland becomes a doomed love affair and her life ends up following a path that starts out as an escape from her parents but becomes a life she freely chooses and values. But there are dark secrets buried in her family's past that eventually come to light. The story vividly encapsulates the troubled relations between the incomers and the aboriginal people, but it is also about families and what makes them, what binds them together and what divides them. Her voice is very immediate, not an old woman recounting the long ago but a young and vibrant character still troubled by the events that have plagued her growing up. I don't want to give too much of the plot away as there are many twists and turns to the events.

Kate Grenville's book The Idea of Perfection was my favourite from last year. Her stories seem to capture very well the thing that is distinct about Australia, not just the unforgiving environment but the impact it has has on the people who went there. She doesn't shy away from dealing with both the tensions between those transported and those who considered themselves true pioneers and the racial tensions that ensued from their invasion. Another wonderful book.

(I confess not from the TBR pilebut picked out so I could listen and knit, am not allowing myself to start a new project until Dunk's jumper is finished.)

Tuesday, 12 March 2013

The Glass Castle

It has been a bit of a Nerdy Non-Fiction year; this is the fifth non-fiction book I have read so far, 'The Glass Castle' by Jeannette Walls. I think this books says a great deal about childhood and family life that challenges my assumptions. It was a very hard read, not the story, that was delightfully told, but to try not to judge them was nigh on impossible, but Jeannette never passes judgement on her parents and so it feels unjustified to do so as a mere reader.

The book tells the story of Jeannette's family life from about the age of four. She seems to have amazing recall of the details of the very early period of her life, recounting events and conversations quite precisely. Their life is everything that society disapproves of, profoundly chaotic and unstable. They live a wandering life, homeless for some periods and moving from place to place often at short notice. They abandon possessions without a care and regularly go hungry. But what is plain is the strength of the bond their family has. Their parent's rejection of the consumerist society is taken to quite an extreme; they do attempt to be self sufficient, never taking state handouts, but frequently running away from debt. Her father is an alcoholic, a fact that dominates family life. He has grand plans to make their life better, including the one to build them a Glass Castle to live in, none of which ever come to anything. Their mother is an artist, who similarly never seems to be short of art supplies (their continued presence is mentioned after every move). It is almost as if they are two people who have made a decision about how they will live their life and the arrival of their children had little impact on the choices or decisions they made, as if they were just more people along for the ride. When they are very young their lifestyle is presented to the children as a grand adventure, and accepted as such, but as they get older they begin to see their life in a different way, to compare it to the lives of others and to want to escape it. Having lived for a period of relative comfort in a house inherited from their grandmother they then move to a shack on a hillside in Welch, West Virginia, where they spend their teenage years. In spite of the deprivations their lives are filled with books, almost a saving grace, that allows them all a means of escapism. I think it is the ultimate example of how you only live on the inside of your own life, that to them how they lived was 'normal', they didn't have the same expectations as other people, and they tended to live amongst other people who were equally poor. Eventually she and her older sister mastermind their escape to New York, in spite of their father stealing their escape fund, and drawing their siblings after them they all eventually make different lives for themselves.

What was curious about my reaction to the book was that I found myself far more harsh in my view of the mother than the father. I did not like either of them, but I judged her for the neglect of her children far more. I judged her because she could have easily provided adequately for them, and chooses not to. There are periods where she works as a teacher but the children have to coax, cajole and support her through the process. And it did not seem to be just an inability to manage money, it is almost a disdain for it, that she would rather life were not like that. They are both so utterly self absorbed. At one point Rex (the father) takes Jeannette to a bar to use as a distraction to the man he is trying to con at pool. I actually thought he was going to prostitute her, and in fact he encourages her to go with the man, simply trusting that she can look after herself (she is about 13 at the time), but not really thinking at all about the situation he puts her in, because all he is interested in is making some money (she at least has the sense to refuse to go again). And then she buys a plastic piggy bank to store their savings in, I saw the outcome of this the minute she said the word piggy bank. The fact that he let them put money in it for nine months before he steals it actually made me think that he was malicious, watching them get their hopes up only to destroy them. And what I found incredible was that she is so naive. She lives with an alcoholic and she leaves this large amount of money in plain sight in their room and doesn't think to hide it. She openly tells her parents about their plan, the mother at least is supportive but the father seems threatened by the idea. All through the story she allows him to continue with this vain idea he has of himself as the head and supporter of a happy family, someone who never lets them down. She supports him in his delusions about himself and their life. But then that is what loving someone is I suppose, and she loves her dad, and I have never lived with an alcoholic. It was the moment when Mary Rose (mother) is hiding in bed eating chocolate when the children having nothing to eat that shocked me the most, that made me think that maybe this woman was not just slightly eccentric but possibly had some kind of deep seated problem. At the end we discover that not only does she still own the house her mother left her but that she owns land that is worth a million pounds, resources which she never used to make her children's lives more bearable. It just felt unnaturally selfish. The sink-or-swim approach to parenting that Rex and Mary Rose operate does seem to have resulted in some well adjusted and resourceful offspring but I can't help but feel that is more by accident than by design. I didn't like the fact that they constantly blamed outside forces for things that went wrong, neither was capable of taking responsibility for anything. I guess that was the aspect that I was judgemental of, not the choices they made, but their utter lack of responsibility. They really lived what they believed, that possessions were unimportant, but they took that one notion to such extremes that it resulted in a life without any material comforts at all. For years they all lived in the shack that rotted and fell apart around them, and yet no one did anything to improve it. Years of moving from place to place had convinced the children that they might up sticks at any time, so what was the point. Jeannette holds her shoes together with safety pins and eats margarine when it is the only food left in the house, and yet she never says she was unhappy. A totally engaging and honest book, certainly not your average life story, related almost matter-of-factly it is the people in it that keep you hooked. A book to make you rethink your attitudes and everything you take for granted in life.

The book tells the story of Jeannette's family life from about the age of four. She seems to have amazing recall of the details of the very early period of her life, recounting events and conversations quite precisely. Their life is everything that society disapproves of, profoundly chaotic and unstable. They live a wandering life, homeless for some periods and moving from place to place often at short notice. They abandon possessions without a care and regularly go hungry. But what is plain is the strength of the bond their family has. Their parent's rejection of the consumerist society is taken to quite an extreme; they do attempt to be self sufficient, never taking state handouts, but frequently running away from debt. Her father is an alcoholic, a fact that dominates family life. He has grand plans to make their life better, including the one to build them a Glass Castle to live in, none of which ever come to anything. Their mother is an artist, who similarly never seems to be short of art supplies (their continued presence is mentioned after every move). It is almost as if they are two people who have made a decision about how they will live their life and the arrival of their children had little impact on the choices or decisions they made, as if they were just more people along for the ride. When they are very young their lifestyle is presented to the children as a grand adventure, and accepted as such, but as they get older they begin to see their life in a different way, to compare it to the lives of others and to want to escape it. Having lived for a period of relative comfort in a house inherited from their grandmother they then move to a shack on a hillside in Welch, West Virginia, where they spend their teenage years. In spite of the deprivations their lives are filled with books, almost a saving grace, that allows them all a means of escapism. I think it is the ultimate example of how you only live on the inside of your own life, that to them how they lived was 'normal', they didn't have the same expectations as other people, and they tended to live amongst other people who were equally poor. Eventually she and her older sister mastermind their escape to New York, in spite of their father stealing their escape fund, and drawing their siblings after them they all eventually make different lives for themselves.

What was curious about my reaction to the book was that I found myself far more harsh in my view of the mother than the father. I did not like either of them, but I judged her for the neglect of her children far more. I judged her because she could have easily provided adequately for them, and chooses not to. There are periods where she works as a teacher but the children have to coax, cajole and support her through the process. And it did not seem to be just an inability to manage money, it is almost a disdain for it, that she would rather life were not like that. They are both so utterly self absorbed. At one point Rex (the father) takes Jeannette to a bar to use as a distraction to the man he is trying to con at pool. I actually thought he was going to prostitute her, and in fact he encourages her to go with the man, simply trusting that she can look after herself (she is about 13 at the time), but not really thinking at all about the situation he puts her in, because all he is interested in is making some money (she at least has the sense to refuse to go again). And then she buys a plastic piggy bank to store their savings in, I saw the outcome of this the minute she said the word piggy bank. The fact that he let them put money in it for nine months before he steals it actually made me think that he was malicious, watching them get their hopes up only to destroy them. And what I found incredible was that she is so naive. She lives with an alcoholic and she leaves this large amount of money in plain sight in their room and doesn't think to hide it. She openly tells her parents about their plan, the mother at least is supportive but the father seems threatened by the idea. All through the story she allows him to continue with this vain idea he has of himself as the head and supporter of a happy family, someone who never lets them down. She supports him in his delusions about himself and their life. But then that is what loving someone is I suppose, and she loves her dad, and I have never lived with an alcoholic. It was the moment when Mary Rose (mother) is hiding in bed eating chocolate when the children having nothing to eat that shocked me the most, that made me think that maybe this woman was not just slightly eccentric but possibly had some kind of deep seated problem. At the end we discover that not only does she still own the house her mother left her but that she owns land that is worth a million pounds, resources which she never used to make her children's lives more bearable. It just felt unnaturally selfish. The sink-or-swim approach to parenting that Rex and Mary Rose operate does seem to have resulted in some well adjusted and resourceful offspring but I can't help but feel that is more by accident than by design. I didn't like the fact that they constantly blamed outside forces for things that went wrong, neither was capable of taking responsibility for anything. I guess that was the aspect that I was judgemental of, not the choices they made, but their utter lack of responsibility. They really lived what they believed, that possessions were unimportant, but they took that one notion to such extremes that it resulted in a life without any material comforts at all. For years they all lived in the shack that rotted and fell apart around them, and yet no one did anything to improve it. Years of moving from place to place had convinced the children that they might up sticks at any time, so what was the point. Jeannette holds her shoes together with safety pins and eats margarine when it is the only food left in the house, and yet she never says she was unhappy. A totally engaging and honest book, certainly not your average life story, related almost matter-of-factly it is the people in it that keep you hooked. A book to make you rethink your attitudes and everything you take for granted in life.

Saturday, 9 March 2013

Mass Instruction (weapons thereof)

Most people don't realise that compulsory schooling has only been around in western society for a relatively brief period of time, since around 1870. John Taylor Gatto has been around and writing about the evils of school for over twenty years now, having worked within the system, and received awards for doing so, for thirty before that. 'Weapons of Mass Instructions' is his latest offering, and though he has a tendency to circle around and around the same arguments he does present them in a very informal and readable way. They are all arguments I am familiar with so you'll have to excuse the slightly haphazard collection of quotes that I will use to sum them up. Many years ago he sent me a preview copy of his weighty tome The Underground History of American Education (that can now be downloaded in full here), not that we were on first name terms or anything, I was just actively involved in Education Otherwise at the time and he probably pulled my contact details from the newsletter. It was a detailed history of the education system enmeshed with his own life history and experiences. This one has much the same style, skirting around some of his own teaching experiences and giving example after example of people who go their own way and what they achieve by doing so.

In a potted version of the earlier Underground History he begins his thesis by giving us the state of America prior to compulsory schooling :

"Long before this habit training took hold, America was, by any historical yardstick, formidably well-educated, a place of aggressively free speech and argument - dynamically entrepreneurial, dazzlingly inventive, and as egalitarian a place as human nature could tolerate." (p.17)

I found his view a little idealised (I wonder if it is his way of demonstrating he is not being un-american in his critique of such a fundamental part of their society) but he then goes on to explain how a centralised school system was imposed on a reluctant population. He claims it's purpose:

"But in the new fashion, different goals were promulgated, goals for which self-reliance, ingenuity, courage, competence, and other frontier virtues became liabilities (because they threatened the authority of management). Under the new system, the goals of good moral values, good citizenship and good personal development were exchanged for a novel fourth purpose - becoming a human resource to be spent by businessmen and politicians." (p23)

and backs it up with this quote from Woodrow Wilson from 1909:

"We want one class to have a liberal education. We want another class, a very much larger class of necessity, to forgo the privilege of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks." (p.23)

And thus:

"From 1880 to 1930, the term 'overproduction' was heard everywhere, in boardrooms, elite universities, gentleman's clubs and highbrow magazines. It was a demon which had to be locked in the dungeon. And rationalised pedagogy was a natural vehicle to implant habits and attitudes to accomplish that end. Under this outlook, the classroom would never be used to produce knowledge, but only to consume it; it would not encourage the confined to produce ideas, only to consume the ideas of others. The ultimate goal implanted in student minds, which replaced the earlier goal of independent livelihoods, was getting a good job." (p25)

Gatto is a big proponent of what he terms 'open source' learning, people pursuing their own ideas and fascinations and eschewing formal teaching situations. He gives example after example of people who did just that, from Richard Branson, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and the likes, to a student of his called Stanley who ditched school in favour of learning the trades of various family members:

"A big secret of bulk-process schooling us that it doesn't teach the way children learn; a bigger secret is that it isn't supposed to teach self-direction at all. Stanley-style is verboten. School is about learning to wait your turn, however long it takes to come, if ever. And how to submit with a show of enthusiasm to the judgement of strangers, even if they are wrong; even if your enthusiasm is phoney.

School is the first impression we get of organised society and its relentless need to rank everyone on a scale of winners and losers; like most first impressions, the real things school teaches about your place in the social order last a lifetime for most of us." (p.63)

He talks about resistance from without, like the Amish community in Wisconsin fighting to preserve their way of life and values, and how little resistance there was from within:

"Once a principal in the richest secondary school in District Three asked me privately if I could help him set up a program to teach critical thinking. Of course, I replied, but if we do it right your school will become unmanageable. Why would kids taught to think critically and express themselves effectively put up with the nonsense you force down their throats? That was the end of our interview and his critical thinking project." (p.76)

John himself found many and various ways to allow his students to escape the confines of both the imposed curriculum and the school building and away also from what he saw as the enforced passivity of television consumption:

"I set out to shock my students into discovering that face to face engagement with reality was more interesting and rewarding than watching the pre-packaged world of media screens, my target was helping them jettison the lives of spectators which had been assigned to them, so they could become players. I couldn't tell anyone in the school universe what I was doing, but I made strenuous efforts to enlist parents as active participants. ...

Plunging kids into the nerve-wracking, but exhilarating waters of real life - sending them on expeditions across the state, opening the court system to their lawsuits, and the economy to their businesses, filling public forums with their speeches and political action - made them realise, without lectures, how much of their time was customarily wasted sitting in the dark." (p.93)

His own attempts at resistance and his aims to spread his ideas and understanding has on occasion been met with quite virulent opposition. He recites an incident when speaking at a prosperous high school about the realities of SAT scores, college admissions and the myths of schooling and the event was literally bought to a halt by the school superintendent calling in the police; the scene is quite surreal and yet quite believable.

He quotes this lovely analogy from a young man called Andrew Hsu who he met at an award ceremony, it captures so perfectly pretty much everything the book tries to say. It concerns the training of fleas:

"If you put a flea in a shallow container they jump out. But if you put a lid on the container for just a short time, they hit the lid trying to escape and learn quickly not to jump so high. They give up their quest for freedom. After the lid is removed, the fleas remain imprisoned by their own self-policing. So it is with life. Most of us let our own fears or the impositions of others imprison us in a world of low expectations." (p.141)

The one thing I find annoying about his approach and use of 'shining' examples, young people sailing singlehanded around the globe or setting up successful businesses or making amazing scientific discoveries, is that he ends up implying that opting out of the school system is only ok if you end up doing something remarkable. It is ok to opt out and just be ordinary, to just live an ordinary life that is of your choosing. Compulsory school is not just a waste of time for geniuses and creative types, it is a waste of time for everybody, it crushes the life out of the unassuming ones too. (Also politically he is a bit of a libertarian, an admirer of free market economics and does not seem interested in political change. For me it seems logical to extend the argument into other areas of life.) It is something that the whole home education community is guilty of to a certain extent, to point vociferously to the success stories as a justification for our opinions and existence, as if we have to be better than school, that our children have to get better exam results so that we can say 'look, we should be permitted to do what we do because we achieve within the confines of your narrow definition of success'.

While I think that 'Dumbing Us Down' is a better book (and I will get around the rereading and reviewing it some time), it dwells less on history and more on an examination of the effect of schooling on the individual, I find that what I continue to like most about Gatto is that he just pursues the ideas. He keeps pushing and repeating, hoping that in the end more and more people will finally get the message. He ends the main section of the book thus:

"I hope this has been enough to continue weapon-hunting on your own. Writing this has made me so sad and angry. I can't continue."

Sometimes I still feel sad and angry about schools, but so long as there are people out there telling it like it is there has to be hope.

(Fourth book in the TBR pile challenge 2013)

In a potted version of the earlier Underground History he begins his thesis by giving us the state of America prior to compulsory schooling :

"Long before this habit training took hold, America was, by any historical yardstick, formidably well-educated, a place of aggressively free speech and argument - dynamically entrepreneurial, dazzlingly inventive, and as egalitarian a place as human nature could tolerate." (p.17)

I found his view a little idealised (I wonder if it is his way of demonstrating he is not being un-american in his critique of such a fundamental part of their society) but he then goes on to explain how a centralised school system was imposed on a reluctant population. He claims it's purpose:

"But in the new fashion, different goals were promulgated, goals for which self-reliance, ingenuity, courage, competence, and other frontier virtues became liabilities (because they threatened the authority of management). Under the new system, the goals of good moral values, good citizenship and good personal development were exchanged for a novel fourth purpose - becoming a human resource to be spent by businessmen and politicians." (p23)

and backs it up with this quote from Woodrow Wilson from 1909:

"We want one class to have a liberal education. We want another class, a very much larger class of necessity, to forgo the privilege of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks." (p.23)

And thus:

"From 1880 to 1930, the term 'overproduction' was heard everywhere, in boardrooms, elite universities, gentleman's clubs and highbrow magazines. It was a demon which had to be locked in the dungeon. And rationalised pedagogy was a natural vehicle to implant habits and attitudes to accomplish that end. Under this outlook, the classroom would never be used to produce knowledge, but only to consume it; it would not encourage the confined to produce ideas, only to consume the ideas of others. The ultimate goal implanted in student minds, which replaced the earlier goal of independent livelihoods, was getting a good job." (p25)

Gatto is a big proponent of what he terms 'open source' learning, people pursuing their own ideas and fascinations and eschewing formal teaching situations. He gives example after example of people who did just that, from Richard Branson, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and the likes, to a student of his called Stanley who ditched school in favour of learning the trades of various family members:

"A big secret of bulk-process schooling us that it doesn't teach the way children learn; a bigger secret is that it isn't supposed to teach self-direction at all. Stanley-style is verboten. School is about learning to wait your turn, however long it takes to come, if ever. And how to submit with a show of enthusiasm to the judgement of strangers, even if they are wrong; even if your enthusiasm is phoney.

School is the first impression we get of organised society and its relentless need to rank everyone on a scale of winners and losers; like most first impressions, the real things school teaches about your place in the social order last a lifetime for most of us." (p.63)

He talks about resistance from without, like the Amish community in Wisconsin fighting to preserve their way of life and values, and how little resistance there was from within:

"Once a principal in the richest secondary school in District Three asked me privately if I could help him set up a program to teach critical thinking. Of course, I replied, but if we do it right your school will become unmanageable. Why would kids taught to think critically and express themselves effectively put up with the nonsense you force down their throats? That was the end of our interview and his critical thinking project." (p.76)

John himself found many and various ways to allow his students to escape the confines of both the imposed curriculum and the school building and away also from what he saw as the enforced passivity of television consumption:

"I set out to shock my students into discovering that face to face engagement with reality was more interesting and rewarding than watching the pre-packaged world of media screens, my target was helping them jettison the lives of spectators which had been assigned to them, so they could become players. I couldn't tell anyone in the school universe what I was doing, but I made strenuous efforts to enlist parents as active participants. ...

Plunging kids into the nerve-wracking, but exhilarating waters of real life - sending them on expeditions across the state, opening the court system to their lawsuits, and the economy to their businesses, filling public forums with their speeches and political action - made them realise, without lectures, how much of their time was customarily wasted sitting in the dark." (p.93)

His own attempts at resistance and his aims to spread his ideas and understanding has on occasion been met with quite virulent opposition. He recites an incident when speaking at a prosperous high school about the realities of SAT scores, college admissions and the myths of schooling and the event was literally bought to a halt by the school superintendent calling in the police; the scene is quite surreal and yet quite believable.

He quotes this lovely analogy from a young man called Andrew Hsu who he met at an award ceremony, it captures so perfectly pretty much everything the book tries to say. It concerns the training of fleas:

"If you put a flea in a shallow container they jump out. But if you put a lid on the container for just a short time, they hit the lid trying to escape and learn quickly not to jump so high. They give up their quest for freedom. After the lid is removed, the fleas remain imprisoned by their own self-policing. So it is with life. Most of us let our own fears or the impositions of others imprison us in a world of low expectations." (p.141)

The one thing I find annoying about his approach and use of 'shining' examples, young people sailing singlehanded around the globe or setting up successful businesses or making amazing scientific discoveries, is that he ends up implying that opting out of the school system is only ok if you end up doing something remarkable. It is ok to opt out and just be ordinary, to just live an ordinary life that is of your choosing. Compulsory school is not just a waste of time for geniuses and creative types, it is a waste of time for everybody, it crushes the life out of the unassuming ones too. (Also politically he is a bit of a libertarian, an admirer of free market economics and does not seem interested in political change. For me it seems logical to extend the argument into other areas of life.) It is something that the whole home education community is guilty of to a certain extent, to point vociferously to the success stories as a justification for our opinions and existence, as if we have to be better than school, that our children have to get better exam results so that we can say 'look, we should be permitted to do what we do because we achieve within the confines of your narrow definition of success'.

"I hope this has been enough to continue weapon-hunting on your own. Writing this has made me so sad and angry. I can't continue."

Sometimes I still feel sad and angry about schools, but so long as there are people out there telling it like it is there has to be hope.

(Fourth book in the TBR pile challenge 2013)

Labels:

book review,

challenges,

education,

EO,

non-fiction,

politics,

school

Friday, 8 March 2013

Miserable in Croydon

Lost and Found by Tom Winter

I am just going to write a quickie about this book that I requested on recommendation, laughed over the first page so kept reading but was just annoyed by before the first chapter was up. The only intriguing aspect was the plot line, mostly because of my philosophy course, because here we have two people living unexamined lives, so it then begged the question, are these lives worth living?

Carol is unhappily married to a man who turns out to have cancer, so she chickens out of leaving him. Albert is a lonely postman (we don't wear those hats any more by the way, his uniform is from the 1950s), spending 40 years mourning his wife. A life spent unhappily (according to Socrates that is) is of necessity an unexamined one, since people do not wish harm to themselves and therefore, if they reflected upon their situation would do something to alter it. Neither of them seems to have done anything to change things for quite a long time. The process of their chance 'encounter' with each other does seem to finally be bringing about some reflection, maybe better late than never, but that's not really what's wrong with the book.

It would have taken the author about ten seconds of research to discover that, firstly post is delivered by Royal Mail not the Post Office, hasn't been called that in god knows how many years, and more importantly that we do not have little rooms in each office where we store dusty bags of undelivered mail. All undeliverable or returned mail is sent to a processing centre in Belfast and not handled by individual offices or mail centres, so there is no way that Albert would be sidelined into a little back room and told to sort dead letters for disposal. And yes, it would be a sackable offence to remove mail from the office and take it home, and a postman of his experience would never consider doing such a thing, no matter how curious he might be (and by the way, just to reassure readers, mostly we don't have a second to spare to be curious about the contents of anyone's letters).

Next awful thing about the book, the parade of terrible lazy clichéd characters:

overworked distracted manager with clipboard,

self-absorbed best friend who drinks weird herbal tea and must therefore bake inedible things using oatmeal,

overweight angry lesbian teenage daughter,

overly studious superior teenage daughter,

air-headed next-door-neighbour with misogynistic husband,

smarmy private doctor,

narrow-minded religious mother,

bullying next door neighbour,

and not one, but two over-idealised deceased loved ones.

Then the author makes Albert do something very mean and spiteful, just so totally out of character, and if it hadn't been so close to the end I would have abandoned it then. He then seems to make Albert fall ill, as if for no other reason than to bring in the social worker to cheer him up a bit (And another thing, they wouldn't give him a Royal Mail coat as a retirement gift. Uniform belongs to the company and is only worn by employees and should be returned if you leave since it could be used to defraud people by pretending to be a postman.) He ties it all up neat and tidy in the end, pairing everyone off with new loved ones, except poor Albert who writes letters to the studious daughter and that somehow makes his retirement content and makes up for a lifetime of loneliness. So no, not really a whole lot of life examination going on. Not very often I do a total hatchet job but there you go. An unremarkable book.

I am just going to write a quickie about this book that I requested on recommendation, laughed over the first page so kept reading but was just annoyed by before the first chapter was up. The only intriguing aspect was the plot line, mostly because of my philosophy course, because here we have two people living unexamined lives, so it then begged the question, are these lives worth living?

Carol is unhappily married to a man who turns out to have cancer, so she chickens out of leaving him. Albert is a lonely postman (we don't wear those hats any more by the way, his uniform is from the 1950s), spending 40 years mourning his wife. A life spent unhappily (according to Socrates that is) is of necessity an unexamined one, since people do not wish harm to themselves and therefore, if they reflected upon their situation would do something to alter it. Neither of them seems to have done anything to change things for quite a long time. The process of their chance 'encounter' with each other does seem to finally be bringing about some reflection, maybe better late than never, but that's not really what's wrong with the book.

It would have taken the author about ten seconds of research to discover that, firstly post is delivered by Royal Mail not the Post Office, hasn't been called that in god knows how many years, and more importantly that we do not have little rooms in each office where we store dusty bags of undelivered mail. All undeliverable or returned mail is sent to a processing centre in Belfast and not handled by individual offices or mail centres, so there is no way that Albert would be sidelined into a little back room and told to sort dead letters for disposal. And yes, it would be a sackable offence to remove mail from the office and take it home, and a postman of his experience would never consider doing such a thing, no matter how curious he might be (and by the way, just to reassure readers, mostly we don't have a second to spare to be curious about the contents of anyone's letters).

Next awful thing about the book, the parade of terrible lazy clichéd characters:

overworked distracted manager with clipboard,

self-absorbed best friend who drinks weird herbal tea and must therefore bake inedible things using oatmeal,

overweight angry lesbian teenage daughter,

overly studious superior teenage daughter,

air-headed next-door-neighbour with misogynistic husband,

smarmy private doctor,

narrow-minded religious mother,

bullying next door neighbour,

and not one, but two over-idealised deceased loved ones.

Then the author makes Albert do something very mean and spiteful, just so totally out of character, and if it hadn't been so close to the end I would have abandoned it then. He then seems to make Albert fall ill, as if for no other reason than to bring in the social worker to cheer him up a bit (And another thing, they wouldn't give him a Royal Mail coat as a retirement gift. Uniform belongs to the company and is only worn by employees and should be returned if you leave since it could be used to defraud people by pretending to be a postman.) He ties it all up neat and tidy in the end, pairing everyone off with new loved ones, except poor Albert who writes letters to the studious daughter and that somehow makes his retirement content and makes up for a lifetime of loneliness. So no, not really a whole lot of life examination going on. Not very often I do a total hatchet job but there you go. An unremarkable book.

Birthday reflections and Fibre Arts Friday

So yesterday was my 21st birthday (again). I got despondent in my mid thirties about the advancing years and so decided to start counting backwards, and as with such things the offspring have continued to find it amusing, consequently Creature made me a 21st birthday cake.

Mum and dad sent me this most beautiful enamelled pendant from a craft event at Bovey Tracey, made by an artist called Janine Partington. As I said to mum on the phone it is the most perfect of presents as I would have seen it and thought how lovely but never bought it for myself. I gave up wearing much in the way of jewellery when the children were tiny since babies always got their fingers tangled in necklaces (and who has time in the morning to choose body decoration with four small children demanding food), so maybe now is the time to start again.I had a plan to write myself a 'before I'm 50' bucket-list-type-thing of stuff to try and work on/achieve/whatever over the next year but I didn't want it to be a 'go bungee jumping/skydiving/walk the great wall of china' thing (mainly because I have no money, but also because I am not that into heights:-) Anyway I made a list that is more like new year resolutions than buckets:

- submit something to the Bridport Prize competition

- learn some poetry by heart

- spend more time reading and less on the computer

- systematically look for a new job

- stick with the zumba

- go to the theatre

- go back to the felting and spinning, much neglected in the last year

I have started doing a course on Coursera entitled Know Thyself, a mixture of philosophy, psychology, psychoanalysis, neuroscience, aesthetics and Buddhism (as the description says), run by the University of Virginia. I have started (yet another) blog as a place to put the 'assignments', though strictly the assignments are for your own benefit and you pass the course by passing the online tests each week, but I feel like what is the point if you don't give some real thought to the questions they are raising. So far, so interesting.

Since today is Friday please also pop over (for those craftily inclined) to Fibre Arts Friday and see the shares. I have spun one hank of the roving that I dyed last week and am very pleased with it. I only use a spindle and just spin singles, I have no idea how to go about plying. Not sure I will knit anything with it any time soon as Dunk has been hinting for his jumper and I have a plan for a knitted dress that we found in one of Julie's magazines.

Friday, 1 March 2013

Kool-Aid dyeing for Fibre Arts Friday

I have been very lacking in creative inclination in the last few months. I tried making a pair of felt slippers for Creature at the weekend but they came out too small so will have to start again. However in digging through the box of roving I found the packets of Kool-Aid that Julie bought back from America two years ago, and so I decided to do some dyeing (vaguely following the instructions here on Knitty.) It's slightly worrying that some people feed this stuff to their children, it really is the ultimate non-food 'food'.

This is about 5oz of fleece roving, just soaked in cold water.

The instructions say you do not need extra acid to fix as the Kool-aid is pretty acidic.

1 pack per 1oz of fleece or yarn, so I made up 2 packs strawberry, 2 packs cherry

and 1 pack blackcurrant, each in a glassful of water.

This batch has all three colours:

This batch has just the cherry and strawberry, it looks all the same but one is more pinky:

They were both heated in the microwave for 8 minutes, in two minute chunks with a rest while the other was heated. The instructions said a mere 4 minutes but suggested you keep going until the colour is absorbed and the water is clear; you can see here all the dye has been absorbed:

I left them to cool then washed and rinsed gently, squeezing as much water out as possible

(do not wring or swish about too much to avoid felting)

Here are the two hanks, one is about 3oz, the other about 2oz

Close up of the lovely soft colours:

Hope to do a bit of spinning before next week.

We are going to see if it works just as well on Creature's hair:-)

(Linking back to Fibre Arts Friday where you can visit other creative wonders.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)