Wednesday 27 December 2023

Being Dead?

Sunday 24 December 2023

Crimbo Time

I am not sure how much I have read this year ... so lets see ...

Must I Go by Yiyun Li

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Long Live the Post Horn by Vigdis Hjorth

Diary of a Void by Emi Yagi

Otherlands by Thomas Halliday

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

A Tidy Ending by Joanna Cannon

If Cats Disappeared from the World by Genki Kawamura

Forget Me Not by Sophie Pavelle

Chorus by Rebecca Kauffman

The Last Resort by Jan Carson

The Reservoir Tapes by John Mcgregor

Old God's Time by Sebastian Barry

A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ni Ghriofa

How to be Human by Paula Cocozza

The Book of Goose by Yiyun Li

Various Poetry

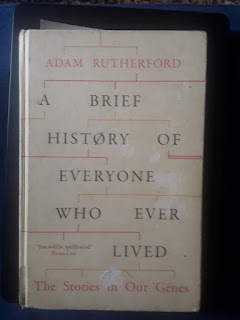

A Brief History of Everyone who ever Lived by Adam Rutherford

My Friend Anne Frank by Hannah Pick-Goslar

Elena Knows by Claudia Pineiro

Resistance by Anita Shreve

Hard by a Great Forest by Leo Vardiashvili

Lonely Castle in the Mirror by Mizuki Tsujimura

Wild Things by Laura Kay

A Lost Lady by Willa Cather

The Hero of this Book by Elizabeth McCracken

Quilt by Nicholas Royle

A Widow for One Year by John Irving

The Zoo of the New

The Power by Naomi Alderman

The Future by Naomi Alderman

That is not a lot of books ... but you know what, I don't beat myself up about how I have spent that last year. I am not sure that I have a favourite from this year's reading, lots of things I enjoyed but nothing stands out for me looking down the list.

Wishing regular readers and random visitors Merry Christmas.

Sunday 10 December 2023

The Future

Tuesday 5 December 2023

Winter Garden

Sunday 3 December 2023

Meanwhile, in Japan ...

Saturday 25 November 2023

The Power

'The Power' by Naomi Alderman won the Women's Fiction Prize in 2017. At one point I did a challenge to read all the winners but I have not kept it up in recent years and there are four that I have not read (but probably still will at some point). The Power is a pretty scary book. What might happen if women suddenly find they have the power to inflict pain on others ... will they behave just like men do? It turns out that power does corrupt. A young woman finds she can produce electricity from a mysterious skein organ across her collarbone, and with practice can target and control it. Soon more women can, and younger women can awaken the power in older women. There ensues a fight for control of the human race. Men try to cling to their millennia old position but you can see where it is all going to end. A new religion is born and wars begin. Some women just go mad with their new found freedom. The tale is told in retrospect ... somewhat I suddenly realise, like Handmaid's Tale, but by a man, who has researched and written a book about the period of transformation. His editor suggests he might want to use a woman's name, to add credibility to his narrative. That's all really. So much going on in the story, lots of strong women characters of course, but not lacking in men, and utterly gripping. Fantastical but also utterly believable.

"Late at night in a part of town that she knows has no surveillance cameras, Margot parks her car, gets out, puts her palm to a lamp post and gives it everything she's got. She just needs to know what she's got under the hood here; she wants to feel what it is. It feels as natural as anything she's ever done, as known and understood as the first time she had sex, as her body saying, Hey, I got this.

All the lights in the road go out: pop, pop, pop. Margot laughs out loud, there in the silent street. She'd be impeached if anyone found out, but then she'd be impeached anyway if anyone knew she could do it at all, so what's the margin? She guns the gas and drives off before the sirens start. She wondered what she'd have done if they'd caught her, and in the asking she knows she has enough left in her skein to stun a man, at least, maybe more - can feel the power sloshing across her collarbone and up and down her arms. The thought makes her laugh again. She finds she's doing that more often now, just laughing. There's a sort of constant ease, as if it's high summer all the time inside her." (p.64)

Stay safe. Be kind. Don't let the bastards grind you down.

Saturday 18 November 2023

Library books and not-library books

'The Zoo of the New' has been a lovely large anthology of poems edited by Nick Laird and Don Paterson. It covers a few hundred years (so a lot of poetry) and mixes up old favourites with undiscovered gems. I stated off reading them all, as I often do and then began to flick through and pick and choose. I still managed to pick out lots that I enjoyed so now I'll have to find just one ...

Tuesday 7 November 2023

Pre-Christmas post - postage and scams

Beware. It's nearly Crimbo time so the scammers are going to be out in force. I have had several people in recently with messages about missed deliveries. Beware of any message that does not include a tracking number. If you are expecting a package check with any dispatch confirmation you might have been sent that will provide tracking information. Messages might refer to a specific delivery company or might be vague. Some messages include a delivery driver's name in order to seem more authentic. Any message that asks for money outright is a scam. I don't know about other companies but Royal Mail never asks for payment for redelivery. Some ask for a very nominal sum, this is because it is your bank details they are after. If you click any link or supply details to any scam website, contact your bank immediately. The Royal Mail website has lots of examples of scam texts and emails:

Thursday 26 October 2023

The Hero of this Book

Elizabeth McCracken is a novelist, not a memoirist, but I found her firstly in 'An Exact Replica ...' nearly a decade ago, swiftly followed by 'The Giant's House'. 'The Hero of This Book' is a novelisation of her relationship with her extraordinary mother. In the story the narrator retraces some of her final times spent with her mother, and navigates the grief of losing a much loved parent. There was so much to love about this book, so here come a bunch of quotes, because the story reflects thoughtfully on loss, parents and life in general. This first one I liked, because it makes a distinction about different kinds of loss:

"Condoling friends used the words grief and mourning. But neither was what I felt. All my life I'd heard people use those words to discuss the ordinary deaths of elderly people - or, worse, elderly animals - and (I am hard-hearted) I found them melodramatic. Those old people and dogs were never going to be immortal. Grief, as I understood it - grief and I were acquainted - is the kind of loss that sets you on fire as your struggle to put it out. My mother's death hadn't changed my mind. I just missed her. I hated to see her go. But she's had a sweet end, or so I kept telling people, though who was I to speak for my mother? She'd hate that, my opinion about her experience. It was sweet for her family, at home with hospice nurses and cats, and friends around the bed, at the time - 2018 - when you couldn't count on a sweet end but it wasn't impossible." (p.5)

What her mother didn't approve of:

"I took her hand. I did this without permission. My mother was not a hand-holder. I sat by her bed. I said, 'I'm sorry this happened to you.' Without permission. I found her dear in her reduced state. I called her honey. I kissed her hello and goodbye. I can't imagine she approved of any of it.

Not this, either: typing sentences about her, calling her only my mother, as though that were her most important identity. 'I don't approve,' she said, of Barbie dolls, and certain flavors of bagels, and all bagels cut in half, and eating anything but the traditional pies on Thanksgiving; she disapproved of fiction written specifically for young adults (she believed they should be reading William Saroyan) and tutus on small girls. She enjoyed being a crank." (p.62-3)

This lovely interaction in a corner shop:

"I thought about buying cigarettes - I smoke sometimes when I travel - but they were kept behind doors, so you couldn't look at brands and then say casually 'Silk cut, please.' You had to be a serious smoker with a plan, and I wasn't. Years before I'd been a devotee of the English ten-pack; a lovely thing, to be able to buy just ten cigarettes at a time. Like my father before me, I fooled myself when it came to bad behaviour. I worried that the young woman behind the store counter wouldn't like me if I asked. For anything large, I don't worry about judgement. Only for the cigarettes, the 10:30am prosecco. Only going on a Ferris wheel by myself, alone and middle-aged. She had a pretty, lupine face.

I pretended I didn't speak the language, put my sandwich and brownie on the counter, and paid in coins, which I counted out as though I were unfamiliar with the notion of money. I tried to look worthy of kindness." (p.92)

And the trials of old age, to be resisted at all costs:

"But her and my mother knew: When you're old, safety is overrated. Safety is the bossy Irish lady, who is, after all, your employee, taking away your wineglass, saying, 'That's enough, that's enough now, that's enough now, darlin'.' Safety puts you in a nursing home and turns you over regularly so that you do not die in your sleep. You could be kept for years if you weren't careful , like a roped-off chair in a museum that nobody is allowed to sit in, which makes it only something shaped like a chair. Watch out for safety. It will make you no longer yourself, only an object shaped that way." (128-9)

The narrator has a lovely visit to London, relishing doing things alone. Relishing things she might not have done with her mother. Missing her mother, but enjoying her activities while thinking how she had loved doing them with her mother, recalling her mother's exuberant enjoyment of life.

It's a story, it's not a memoire about Elizabeth's mother, but I hope it nearly is.

Stay safe. Be kind. Mum's are the best.

Tuesday 3 October 2023

October Flowers

Sunday 1 October 2023

A Guest is a Gift from God

Monday 25 September 2023

Mantis Shrimp

Tuesday 29 August 2023

Friendship

Monday 21 August 2023

Butt-faced Miscreant

Saturday 19 August 2023

Weddings and all that

We're all related to Charlemagne

Tuesday 8 August 2023

Much poetry

.jpeg)