I waited in the library queue for many months for 'Foxlowe' by Eleanor Wasserberg. Simon Savage reviewed it back in the summer and I regularly trust his recommendations. The book is about a community of people who share a mouldering old house and appear on the surface to share a philosophy about life, but in fact are controlled quite blatantly by Freya, who has created a mythology around the 'Bad' outside and the protective qualities of the local stone circle and its magical solstice sunset. The story is told by Green and focusses on the lives of the three children, herself, Toby and her little sister Blue, and their growing up, isolated from, suspicious of, but also curious about, the outside world. You can see immediately that what you are reading about is a cult; the inward looking community is dominated by Freya who's whims and peculiarities are the guiding light of everyone's behaviour, and Leavers are only mentioned in hushed whispers. While it was an engaging story I found myself on the outside looking in, somehow finding it far fetched and a little predictable. There was no depth to any of the other adult characters, they just seemed to people the background. The passage of time is very vague, years seem to go by with no change, except that instead of thriving you have the sense that they are going downhill, there are no resources to pay the water or electricity bill and food often seems scarce. But then the arrival of two women from Social Services sparks a crisis. The rest of the tale is told partly in retrospect by Green, now called Jess, after the breakup of the Family. Her inability to make a new life and a yearning to recreate what has become, for her, an idyllic childhood is something that preoccupies her.

While I think the insidious nature of Freya's control is very well portrayed I felt that the lack in the other adult characters was just a weak way of never having any of them challenge what was going on. It was believable for the children to grow up in this way, but adults with other life experience and their own moral code would not have stayed quiet. I guess I also find gullible and superstitious people a bit annoying and cannot credit why any intelligent person would believe that a circle of salt will protect you from bad stuff. Rejecting society to grow your own food, raise your children in a natural environment and make art is one thing, believing in some weird myths about 'Bad' just left me cold. Having read several of the 'How to spot a psychopath' type articles on the interweb it was patently obvious that Freya is not a well woman and the lasting impact of her behaviour on Green is well telegraphed.

"Of course I knew it would be the Spike Walk straight away, but Freya liked to tease it out. When it was me, she'd come and sit on the bed and ask me how I thought I should be punished, and I'd suggest ways, but it was always the Spike Walk in the end. Somehow it was worse to play the same game for Blue. It was her first time." (p.55)

"She glanced round at everyone, and I followed where she looked, a trick I'd learned. It avoided her gaze, but also made her happy with me, as though I was with her. Dylan was pale and miserable. He looked between Kai, still slumped against the stone, and Freya. Ellen and Pet were biting their nails, their eyes damp. Egg was staring at his feet, his hands in his pockets. Toby knew my trick and stared right back at me, blinking slowly. Blue rocked from foot to foot and ran her thumbnail over her top lip, calming herself." (p.96)

"Freya brought her arm around me, and held up the mirror, just as I had done with Blue. Split by the cracks, our eyes and brows and lips came back to us disassembled, and I saw how much my eyes were Freya's eyes, how they narrowed at the ends, how the lashes didn't curl like Blue's but stuck out long and startling.

- What a beauty you're growing up to be, Freya said.

I smiled and one of the broken lips curled up, showing straight stained teeth.

Freya laughed again, holding her nose, like she was underwater.

- Oh! Poor Green. I don't mean it. You can't see, you're a skinny rag, no flesh on you, your arse is flat and you've no boobs at all, and your hips jut out like knives. But don't worry - she pulled my hair - You're a good girl. Want to keep it? Finders keepers?

I knew the answer to this one.

- No, it's everyone's. I'll put it in Jumble to share, I said." (p.137-8)

"The Family took up this thread guiltily, steering us away to a kinder place, away from the sharp drop of the question of our baby, our youngest sister, becoming a Leaver. We were more indulgent of Blue than was normal, and spoke about how different it was for her, because she didn't know about the world, and we should only try and make her understand, so that she didn't misstep again, and when Freya pointed out that I, Green, was even more of a born Foxlowe girl, but I was good, and I knew how to behave, I could only say, - Blue doesn't have the Bad, she just doesn't. And then the group began to grumble about hunger, and talk turned to food. Freya stepped over Blue and gave her a look that said she hadn't done with her yet, and there would be a Spike Walk for her later, and then gave her a nod to dismiss her." (p.182-3)

So, an interesting and somewhat disturbing coming-of-age tale, a young girl yearning for unconditional love; I was going to say a salutary lesson in the power of nurture over nature, and then I realised that Freya is her mother, so maybe, in this case, it's both.

Sunday, 27 November 2016

Did you mean the Cinema Bookshop or the bookshop cinema?

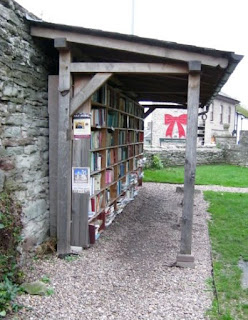

Alternatively titled 'A random hour in Hay on Wye'. Monkey's best friend lives in the middle of the magical bookshop town of Hay. This is the second time I have dropped her off there, but the first time any of the bookshops were open, so despite the fact that I was heading off to my mum's birthday party I could not avoid taking an hour to do a tiny bit of browsing. Bookshops are everywhere, but also just random books are everywhere in Hay. This is one of many 'honesty' shops, in the grounds of Hay Castle; have a browse and put your money in the box, however it could take a long time to find a gem in amongst the rubbish. We only went in a few places, and unfortunately the Poetry Bookshop didn't open till 11. I had a list of some of the books from the 101 Books list that I was hoping to come across but I think that I would need much, much longer.

Some shops have space and order:

Some shops run on pure quirkiness:

This is Addyman Books, where you will find a bat cave, engine parts adorning the stairwells and, as you reach the summit of the building, a bed to rest on in the mountaineering section.

I have long yearned to visit Hay and this was too brief a stopover, I foresee a return trip very soon.

I bought 'Children at the Gate' by Lynne Reid Banks and 'Expensive People' by Joyce Carol Oates.

Friday, 18 November 2016

Bridge Building

Neil Postman wrote a book called 'Teaching as a Subversive Activity' that was a significant influence on me when my children were home educated. I bought 'Building a Bridge to the 18th Century' several years ago and it has been waiting patiently on the list. The book is about the ideas of the 18th century and how they laid the foundation for the modern world and 20th century thinking, and what they still have to offer us in terms of the future: "I do not mean - mind you- technological ideas, like going to the moon, airplanes and antibiotics. We have no shortage of those ideas. I am referring to the ideas of which we can say they have advanced our understanding of ourselves, enlarged our definition of humanness." (p.13-14)

"The eighteenth century is the century of Goethe, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Kant, Hume, Gibbon, Pestalozzi, and Adam Smith. It is the century of Thomas Paine, Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin. In the eighteenth century we developed our ideas of inductive science, about religious and political freedom, about popular education, about rational commerce, and about the nation-state. In the eighteenth century, we also invented the idea of progress, and, you may be surprised to know, our modern idea of happiness. It was in the eighteenth century that reason began to triumph over superstition. And, inspired by Newton, who was elected president of the Royal Society at the beginning of the century, writers, musicians, and artists conceived of the universe as orderly, rational, and comprehensible." (p.17-18)

I read it over several months so have not ended up with a coherent picture of his message, so am going to give you a selection of quotes that I noted as I read. He examines ideas surrounding progress, the use of language to understand ideas:

"We struggle as best we can to connect our words with the world of non-words. Or, at least, to use words that will resonate with the experiences of those whom we address. But one worries, nonetheless, that a generation of young people may become entangled in an academic fashion that will increase their difficulties in solving real problems - indeed, in facing them. Which is why, rather than reading Derrida, they ought to read Diderot, or Voltaire, Rousseau, Swift, Madison, Condorcet, or many of the writers of the Enlightenment period who believed that, for all of the difficulties in mastering language, it is possible to say what you mean, to mean what you say, and to be silent when you have nothing to say. They believed that it is possible to use language to say things about the world that are true - true, meaning they are testable and verifiable, that there is evidence for believing. Their belief in truth included statements about history and about social life, although they knew that such statements were less authoritative than those of a scientific nature. They believed in the capacity of lucid language to help them know when they had spoken truly or falsely. Above all, they believed that the purpose of language is to communicate ideas to oneself and to others. Why, at this point in history, so many Western philosophers are teaching that language is nothing but a snare and a delusion, that it serves only to falsify and obscure, is mysterious to me." (p.80-81)

the place of information and narrative within our culture:

"The problem addressed in the nineteenth century was how to get more information to more people, faster, and in more diverse forms. For 150 years, humanity has worked with stunning ingenuity to solve this problem. The good news is we have. The bad news is that, in solving it, we have created another problem, never before experienced: information glut, information as garbage, information divorced from purpose and even meaning. As a consequence, there prevails amongst us what Langdon Winner calls 'mythinformation' - no lisp intended. It is an almost religious conviction that at the roots of our difficulties - social, political, ecological, psychological - is the fact that we do not have enough information." (p.89)

"Those who speak enthusiastically about the great volume of statements about the world available on the Internet do not usually address how we may distinguish the true from the false. By it's nature, the Internet can have no interest in such a distinction. It is not a 'truth' medium; it is an information medium." (p.92)

"I define knowledge as organised information - information that is embedded in some context; information that has a purpose, that leads one to seek further information in order to understand something about the world. Without organised information, we may know something of the world, but very little about it. When one has knowledge, one knows how to make sense of information, know how to relate information to one's life, and, especially, knows when information is irrelevant.

It is fairly obvious that some newspaper editors are aware of the distinction between information and knowledge, but not nearly enough of them. There are newspapers whose editors do not yet grasp that in a technological world, information is a problems, not a solution. They will tell us things we already know about and will give little or no space to providing a sense of context or coherence." (p.93)

and the role of education and childhood:

"In the Protestant view, the child is an unformed person who, through literacy, education, reason, self-control and shame, may be made into a civilised adult. In the Romantic view, it is not the unformed child but the deformed adult who is the problem. The child possesses as his or her birthright capacities for candour, understanding, curiosity, and spontaneity that are deadened by literacy, education, reason, self-control, and shame." (p.121)

"The whole idea of schooling, now, is to prepare the young for competent entry into the economic life of the community so that they well continue to be devoted consumers." (p.126)

Including an interesting suggestion for the improvement of scientific education:

"The story told by creationists is also a theory. That a theory has its origins in a religious metaphor or belief is irrelevant. Not only was Newton a religious mystic but his conception of the universe as a kind of mechanical clock constructed and set in motion by God us about as religious an idea as you can find. What is relevant is the question, To what extent does a theory meet scientific criteria of validity? The dispute between evolutionists and creation scientists offers textbook writers and teachers a wonderful opportunity to provide students with insights into the philosophy and methods of science. After all, what students really need to know is not whether this or that theory is to be believed, but how scientists judge the merit of a theory. Suppose students were taught the criteria of scientific theory evaluation and then were asked to apply these criteria to the two theories in question. Wouldn't such a task qualify as authentic science education?" (p.168)

It is a hard book to pin down because he covers so many ideas, and often assumes rather a lot of knowledge on the part of his readers, though the book is all the better for that, there is nothing worse than academics dumbing down their thinking. I think it lacked some kind of conclusion, just ending with several appendices of quotations from a wide variety of writers from Lord Byron to George Orwell, and an essay on why television is ruining childhood. This book, reflecting on the impact the current technological revolution is having on our society, was published in 1999 and was Postman's final book, and I can't help but wonder what he might have made of where we are now.

"The eighteenth century is the century of Goethe, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Kant, Hume, Gibbon, Pestalozzi, and Adam Smith. It is the century of Thomas Paine, Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin. In the eighteenth century we developed our ideas of inductive science, about religious and political freedom, about popular education, about rational commerce, and about the nation-state. In the eighteenth century, we also invented the idea of progress, and, you may be surprised to know, our modern idea of happiness. It was in the eighteenth century that reason began to triumph over superstition. And, inspired by Newton, who was elected president of the Royal Society at the beginning of the century, writers, musicians, and artists conceived of the universe as orderly, rational, and comprehensible." (p.17-18)

I read it over several months so have not ended up with a coherent picture of his message, so am going to give you a selection of quotes that I noted as I read. He examines ideas surrounding progress, the use of language to understand ideas:

"We struggle as best we can to connect our words with the world of non-words. Or, at least, to use words that will resonate with the experiences of those whom we address. But one worries, nonetheless, that a generation of young people may become entangled in an academic fashion that will increase their difficulties in solving real problems - indeed, in facing them. Which is why, rather than reading Derrida, they ought to read Diderot, or Voltaire, Rousseau, Swift, Madison, Condorcet, or many of the writers of the Enlightenment period who believed that, for all of the difficulties in mastering language, it is possible to say what you mean, to mean what you say, and to be silent when you have nothing to say. They believed that it is possible to use language to say things about the world that are true - true, meaning they are testable and verifiable, that there is evidence for believing. Their belief in truth included statements about history and about social life, although they knew that such statements were less authoritative than those of a scientific nature. They believed in the capacity of lucid language to help them know when they had spoken truly or falsely. Above all, they believed that the purpose of language is to communicate ideas to oneself and to others. Why, at this point in history, so many Western philosophers are teaching that language is nothing but a snare and a delusion, that it serves only to falsify and obscure, is mysterious to me." (p.80-81)

the place of information and narrative within our culture:

"The problem addressed in the nineteenth century was how to get more information to more people, faster, and in more diverse forms. For 150 years, humanity has worked with stunning ingenuity to solve this problem. The good news is we have. The bad news is that, in solving it, we have created another problem, never before experienced: information glut, information as garbage, information divorced from purpose and even meaning. As a consequence, there prevails amongst us what Langdon Winner calls 'mythinformation' - no lisp intended. It is an almost religious conviction that at the roots of our difficulties - social, political, ecological, psychological - is the fact that we do not have enough information." (p.89)

"Those who speak enthusiastically about the great volume of statements about the world available on the Internet do not usually address how we may distinguish the true from the false. By it's nature, the Internet can have no interest in such a distinction. It is not a 'truth' medium; it is an information medium." (p.92)

"I define knowledge as organised information - information that is embedded in some context; information that has a purpose, that leads one to seek further information in order to understand something about the world. Without organised information, we may know something of the world, but very little about it. When one has knowledge, one knows how to make sense of information, know how to relate information to one's life, and, especially, knows when information is irrelevant.

It is fairly obvious that some newspaper editors are aware of the distinction between information and knowledge, but not nearly enough of them. There are newspapers whose editors do not yet grasp that in a technological world, information is a problems, not a solution. They will tell us things we already know about and will give little or no space to providing a sense of context or coherence." (p.93)

and the role of education and childhood:

"The whole idea of schooling, now, is to prepare the young for competent entry into the economic life of the community so that they well continue to be devoted consumers." (p.126)

Including an interesting suggestion for the improvement of scientific education:

"The story told by creationists is also a theory. That a theory has its origins in a religious metaphor or belief is irrelevant. Not only was Newton a religious mystic but his conception of the universe as a kind of mechanical clock constructed and set in motion by God us about as religious an idea as you can find. What is relevant is the question, To what extent does a theory meet scientific criteria of validity? The dispute between evolutionists and creation scientists offers textbook writers and teachers a wonderful opportunity to provide students with insights into the philosophy and methods of science. After all, what students really need to know is not whether this or that theory is to be believed, but how scientists judge the merit of a theory. Suppose students were taught the criteria of scientific theory evaluation and then were asked to apply these criteria to the two theories in question. Wouldn't such a task qualify as authentic science education?" (p.168)

It is a hard book to pin down because he covers so many ideas, and often assumes rather a lot of knowledge on the part of his readers, though the book is all the better for that, there is nothing worse than academics dumbing down their thinking. I think it lacked some kind of conclusion, just ending with several appendices of quotations from a wide variety of writers from Lord Byron to George Orwell, and an essay on why television is ruining childhood. This book, reflecting on the impact the current technological revolution is having on our society, was published in 1999 and was Postman's final book, and I can't help but wonder what he might have made of where we are now.

Wild Flower Jacket and other crochet

After my foray into crochet a couple of months ago I wanted to progress my skills, so with some wonderful vibrant cotton yarn I made an Augusta shawl as a birthday present for my sister Claire. I learned how to do shaping and a couple of new stitches.

In browsing Ravelry I had come across numerous patterns for circular cardigans and the Wild Flower Jacket became my next project. I managed to order some Drops Alpaca which was completely the wrong weight of yarn for the pattern and so ended up using the yarn doubled, and mixing the shades up so in the end it was perfect because it gave me a bigger variety of colours. It was a very steep learning curve, going from a simple double crochet to “7 ch, then work 4 triple tr tog as follows: Work 2 triple tr in same ch as last triple tr but wait with last YO and pull through on both triple tr, skip 1 dc + 1 ch + 1 dc, work 1 triple tr in next ch but wait with last YO and pull through, then work last triple tr in same ch and pull last YO through all 5 sts on hook”!

The jacket is made all in one piece with holes left to attach the sleeves. I came to very much appreciate the joys of crochet, it grows so much quicker than knitting; it took about a month to make. I felt quite pleased with my new skills as I adapted the pattern by attaching and shaping the sleeves from the top rather than crocheting them separately and sewing them in place. I did not plan the colours, just changing randomly. I used a total of 12 50g balls that cost just under £36, with only a few scraps left that are already being turned into hexipuffs.

I can definitely see a granny square blanket somewhere in my future.

Tuesday, 15 November 2016

Maddaddam

Monkey insisted I read 'Maddaddam' (that I have only just realised is a palindrome) by Margaret Atwood so she could talk about it with me. She has read the trilogy in fairly quick succession whereas it is five years since I read 'The Year of the Flood' and my memory of it was a bit hazy. Where Year of the Flood and Oryx and Crake are set roughly simultaneously 'Maddaddam' follows on pretty much immediately where Year of the Flood leaves off with Toby and Zeb and some of the Gardeners and Maddaddamites trying to build a new community with the Crakers while being threatened variously by some crazed Painballers and the quasi intelligent Pigoons. I love what Margaret Atwood is trying to achieve with this series of books, to imagine the end of civilization and what it would take to start again. The Crakers are Crake's created race of people, supposedly with none of the nasty urges that made human beings such a disaster, but what is really interesting is that despite his best interests the Crakers have, in trying to understand the world better, have build for themselves a mythology around Crake and Orxy as their creators.

Within this book, alongside the ongoing struggle for survival, what we learn is the backstory of Zeb and Adam, who might, or might not be brothers. Zeb relates to Toby and she then becomes the story teller to the Crakers, since Snowman-the-Jimmy is indisposed. So we get the sad tale of their crappy childhood and escape into the underworld and gradually emergence with the support of various agents of resistance.

Here is a description of the Rev, their father, and it sounds freakily familiar:

"The Rev had his very own cult. That was the way to go in those days if you wanted to coin the megabucks and you had a facility for ranting and bullying, plus golden-tongues whip'em-up preaching, and you lacked some other grey-area but highly marketable skills, such a derivative trading. Tell people what they want to hear, call yourself a religion, put the squeeze on for contributions, run your own media outlets and use them for robocalls and slick online campaigns, befriend or threaten politicians, evade taxes. You had to give the guy some credit. He was twisted as a pretzel, he was a tinfoil-halo shit-nosed frogstomping king rat asshole, but he wasn't stupid.

As witness his success. By the time Zeb came along, the Rev had a megachurch, all glass slabbery and pretend oak pews and faux granite, out on the rolling plains. The church of PetrOleum, affiliated with the somewhat more mainstream Petrobaptists. They were riding high for a while, about the time accessible oil became scarce and the price shot up and desperation among the pleebs set in. A lot of top Corps guys would turn up at the church as guest speakers. They'd thank the Almighty for blessing the world with fumes and toxins, cast their eyes upwards as if gasoline came from heaven, look pious as hell." (p.136-7)

The new community, and especially Zeb, somehow keep hoping for the return of Adam, he seemed to be the person with ideas about what should happen next. We just watch the people as they go about rebuilding, while dealing with the normal life things of eating, sleeping and falling in love. They do scavenging runs into the city to get supplies and keep a watch out for the Painballers. In a strange turn of events the Pigoons come to them for help and with the translation assistance of Blackbeard (one of the Craker children) they set up an ambush to deal with their mutual existential threat and reach a mutually beneficial agreement. But there remains the unexplained smoke on the horizon, does it mean there are other humans still out there.

Here Toby is, at the insistence of the Crakers, telling the story:

"The light if fading now, the moths are flying, dusky pink, dusky grey, dusky blue. The Crakers have gathered around Jimmy's hammock. This is where they want Toby to tell the story about Crake and how they came out of the Egg.

Snowman-Ht-Jimmy wants to listen to the story to, they say. Never mind that he's unconscious: they're convinced he can hear it.

They already know the story, but the important thing seems to be that Toby must tell it. She must make a show of eating the fish they've brought, charred on the outside and wrapped in leaves. She must put on Jimmy's ratty red baseball cap and his faceless watch and raise the watch to her hear. She must begin at the beginning, she must preside over the creation, she must lead them out of the Egg and shepherd them down to the seashore.

At the end, they want to hear about the two bad men, and the campfire in the forest, and the soup with the smelly bone in it: they're obsessed with that bone. Then she must tell about how they themselves untied the men, and how the two bad men ran away into the forest, and how they may come back at any time and do more bad things. That part makes them sad, but they insist on hearing it anyway.

Once Toby has made her way through the story, they urge her to tell it again, than again. They prompt, they interrupt, they fill in the parts she's missed. What they want from her is a seamless performance, as well as more information that she either knows or can invent. She's a poor substitute for Snowman-the-Jimmy, but they're doing what they can to polish her up." (p.59-60)

Margaret Atwood's world is wild and creative, it is like ours, at least in the sinister direction ours appears to be heading, though more extreme, with all these surreal creations, but at the same time she provokes you to think about what may become of the world, and if the Crakers are really an 'improvement' on human beings; if you could create a better species, what might it be like?

Within this book, alongside the ongoing struggle for survival, what we learn is the backstory of Zeb and Adam, who might, or might not be brothers. Zeb relates to Toby and she then becomes the story teller to the Crakers, since Snowman-the-Jimmy is indisposed. So we get the sad tale of their crappy childhood and escape into the underworld and gradually emergence with the support of various agents of resistance.

Here is a description of the Rev, their father, and it sounds freakily familiar:

"The Rev had his very own cult. That was the way to go in those days if you wanted to coin the megabucks and you had a facility for ranting and bullying, plus golden-tongues whip'em-up preaching, and you lacked some other grey-area but highly marketable skills, such a derivative trading. Tell people what they want to hear, call yourself a religion, put the squeeze on for contributions, run your own media outlets and use them for robocalls and slick online campaigns, befriend or threaten politicians, evade taxes. You had to give the guy some credit. He was twisted as a pretzel, he was a tinfoil-halo shit-nosed frogstomping king rat asshole, but he wasn't stupid.

As witness his success. By the time Zeb came along, the Rev had a megachurch, all glass slabbery and pretend oak pews and faux granite, out on the rolling plains. The church of PetrOleum, affiliated with the somewhat more mainstream Petrobaptists. They were riding high for a while, about the time accessible oil became scarce and the price shot up and desperation among the pleebs set in. A lot of top Corps guys would turn up at the church as guest speakers. They'd thank the Almighty for blessing the world with fumes and toxins, cast their eyes upwards as if gasoline came from heaven, look pious as hell." (p.136-7)

The new community, and especially Zeb, somehow keep hoping for the return of Adam, he seemed to be the person with ideas about what should happen next. We just watch the people as they go about rebuilding, while dealing with the normal life things of eating, sleeping and falling in love. They do scavenging runs into the city to get supplies and keep a watch out for the Painballers. In a strange turn of events the Pigoons come to them for help and with the translation assistance of Blackbeard (one of the Craker children) they set up an ambush to deal with their mutual existential threat and reach a mutually beneficial agreement. But there remains the unexplained smoke on the horizon, does it mean there are other humans still out there.

Here Toby is, at the insistence of the Crakers, telling the story:

"The light if fading now, the moths are flying, dusky pink, dusky grey, dusky blue. The Crakers have gathered around Jimmy's hammock. This is where they want Toby to tell the story about Crake and how they came out of the Egg.

Snowman-Ht-Jimmy wants to listen to the story to, they say. Never mind that he's unconscious: they're convinced he can hear it.

They already know the story, but the important thing seems to be that Toby must tell it. She must make a show of eating the fish they've brought, charred on the outside and wrapped in leaves. She must put on Jimmy's ratty red baseball cap and his faceless watch and raise the watch to her hear. She must begin at the beginning, she must preside over the creation, she must lead them out of the Egg and shepherd them down to the seashore.

At the end, they want to hear about the two bad men, and the campfire in the forest, and the soup with the smelly bone in it: they're obsessed with that bone. Then she must tell about how they themselves untied the men, and how the two bad men ran away into the forest, and how they may come back at any time and do more bad things. That part makes them sad, but they insist on hearing it anyway.

Once Toby has made her way through the story, they urge her to tell it again, than again. They prompt, they interrupt, they fill in the parts she's missed. What they want from her is a seamless performance, as well as more information that she either knows or can invent. She's a poor substitute for Snowman-the-Jimmy, but they're doing what they can to polish her up." (p.59-60)

Margaret Atwood's world is wild and creative, it is like ours, at least in the sinister direction ours appears to be heading, though more extreme, with all these surreal creations, but at the same time she provokes you to think about what may become of the world, and if the Crakers are really an 'improvement' on human beings; if you could create a better species, what might it be like?

The Lesser Bohemians

I am not sure how to react to Eimear McBride's 'The Lesser Bohemians'. ... This post has been sitting as a draft for a fortnight now and I just want to get the backlog of reviews done...

I was disappointed with this book, and that's a sad thing to say, because it was a lovely book. I did 'enjoy' it more than Girl (this is how Eimear referred to her first book) because it was a warm, mostly positive story, but it lacked something. It did not have the immediacy of Girl, it felt more like the character was relating something that had happened rather than the reader experiencing things in the moment that she managed to achieve so viscerally first time around. It was also the fact that where Girl was about one person, Lesser Bohemians was about two, and I felt the long section in the middle where the man describes his traumatic childhood distracted very much from the reader's experience of what the girl was thinking and feeling. It felt in someways to me, I'm sure others will disagree, that it could have been an alternative future for the girl in the first story. Eimear did talk about how she tried to link the two stories together, with dream elements (though I only noticed this occurring once, maybe I missed it). I found that I bonded much more with the male character (she did give them names but I forget now) over his loss of his daughter, and maybe he almost became a male version of the girl in Girl, falling into this terrible self-destructive behaviour to cope with the desolation he feels. She describes it as a love story, and at its very essence it is the ultimate love story, about no matter where your life has taken you love can redeem all you positive qualities and give you reasons to live.

Here he has snuck into her flat against the orders of a disapproving landlady:

"In the after, I listen to the rain. His breath on my shoulder That was great. And the is how I'd like the night to be - hours of lying here with him - but Don't sleep, I say You have to leave. don't send me back out there. Consider it a punishment for you sins! Bit I'll get up so early. No. An hour? No. Half? No. Five minutes more? Those five he get but after them Up. You're a hard woman, he says getting off, all reluctant. And so I am, watching hinders now in the dark. We kiss a good while though before my door shuts and I listen to no sound on the stairs. Practice makes perfect. But I go to my window. Heavy rain beyond and him coming out into it. Tugging up his collar. Lighting a cigarette. Look up look up. He looks up. I show a hand. In turn, he bows then goes out to the footpath. I follow him to the end of the street where he disappears round Our Lady Help of Christians. Then slip back into the smell of him on my sheets. Search out the last of his taste on my lips. Imagine that I'd kept him here. Then think of him, in the rain, out there. That could - if I wanted - make my heart a little break. but I don't want it to, so it does not." (p.80)

I was disappointed with this book, and that's a sad thing to say, because it was a lovely book. I did 'enjoy' it more than Girl (this is how Eimear referred to her first book) because it was a warm, mostly positive story, but it lacked something. It did not have the immediacy of Girl, it felt more like the character was relating something that had happened rather than the reader experiencing things in the moment that she managed to achieve so viscerally first time around. It was also the fact that where Girl was about one person, Lesser Bohemians was about two, and I felt the long section in the middle where the man describes his traumatic childhood distracted very much from the reader's experience of what the girl was thinking and feeling. It felt in someways to me, I'm sure others will disagree, that it could have been an alternative future for the girl in the first story. Eimear did talk about how she tried to link the two stories together, with dream elements (though I only noticed this occurring once, maybe I missed it). I found that I bonded much more with the male character (she did give them names but I forget now) over his loss of his daughter, and maybe he almost became a male version of the girl in Girl, falling into this terrible self-destructive behaviour to cope with the desolation he feels. She describes it as a love story, and at its very essence it is the ultimate love story, about no matter where your life has taken you love can redeem all you positive qualities and give you reasons to live.

Here he has snuck into her flat against the orders of a disapproving landlady:

"In the after, I listen to the rain. His breath on my shoulder That was great. And the is how I'd like the night to be - hours of lying here with him - but Don't sleep, I say You have to leave. don't send me back out there. Consider it a punishment for you sins! Bit I'll get up so early. No. An hour? No. Half? No. Five minutes more? Those five he get but after them Up. You're a hard woman, he says getting off, all reluctant. And so I am, watching hinders now in the dark. We kiss a good while though before my door shuts and I listen to no sound on the stairs. Practice makes perfect. But I go to my window. Heavy rain beyond and him coming out into it. Tugging up his collar. Lighting a cigarette. Look up look up. He looks up. I show a hand. In turn, he bows then goes out to the footpath. I follow him to the end of the street where he disappears round Our Lady Help of Christians. Then slip back into the smell of him on my sheets. Search out the last of his taste on my lips. Imagine that I'd kept him here. Then think of him, in the rain, out there. That could - if I wanted - make my heart a little break. but I don't want it to, so it does not." (p.80)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)